Migration policy situation during the change of leadership in the European Union

12.08.2019One of the most complex issues facing the incoming European Parliament and Commission is immigration. This was once again confirmed by the European-wide tensions that emerged in response to the UN compact for migration. The new leaders might find some relief in the fact that the number of applicants for international protection as well as irregular immigrants to the EU has fallen to pre-crisis levels. At the same time, those who have been recently granted international protection in the EU still need to be integrated, and the reform of the Common European Asylum System, that should bring greater solidarity and efficiency is still in process. Another huge challenge is returning irregularly staying third-country nationals.

Regular migration

While negotiations on the EU Blue Card have stalled, European countries continue to feel the need for highly-qualified foreign labour. In order to remedy the situation, Member States have developed their own national schemes. More than half of the Member States have simplified the issuance of residence permits / visas to various groups of qualified migrant workers.

Alongside opening up labour migration channels, most Member States were looking for ways to reduce social dumping and labour exploitation. On the one hand, the social status and working conditions of foreign workers were improved; on the other hand, employers and foreign workers were monitored more closely to detect any violations. Police and Border Guard Board, Tax and Customs Board and Labour Inspectorate carried out joint raids on construction sites in 2018.

One of the key groups in 2018 were foreign students — in order to attract them to the country and involve them in the labour market, the so-called Students and Researchers Directive was transposed in May 2018. Inter alia, this sped up the processing of foreign students’ residence applications, improved their opportunities to work during the studies and enabled them to stay in the country after graduating in order to look for employment or start a business. Intra-European mobility of foreign students was likewise facilitated. Foreign students holding a residence permit issued by one Member State now have the right to study in a higher education institution of another Member State at least for one year. It has become clear that Europe is quite successful in attracting foreign students to come and study here, but fails to engage them in employment after they graduate. The latter policy field should be developed across Europe in order to benefit more from the young foreign graduates of our universities.

Last year, many Member States reviewed their plans and strategies for integrating foreign nationals, in order to support the adaptation and integration of primarily those who arrived during the migrant crisis. Educational programmes for foreign nationals (especially language learning programmes) were considerably extended. At the same time, there were awareness-raising campaigns directed at the local population and local officials about the causes of migration and positive effects of immigrants on the development of Europe. This work needs to be continued in order to maintain and improve the social cohesion in European societies.

International protection

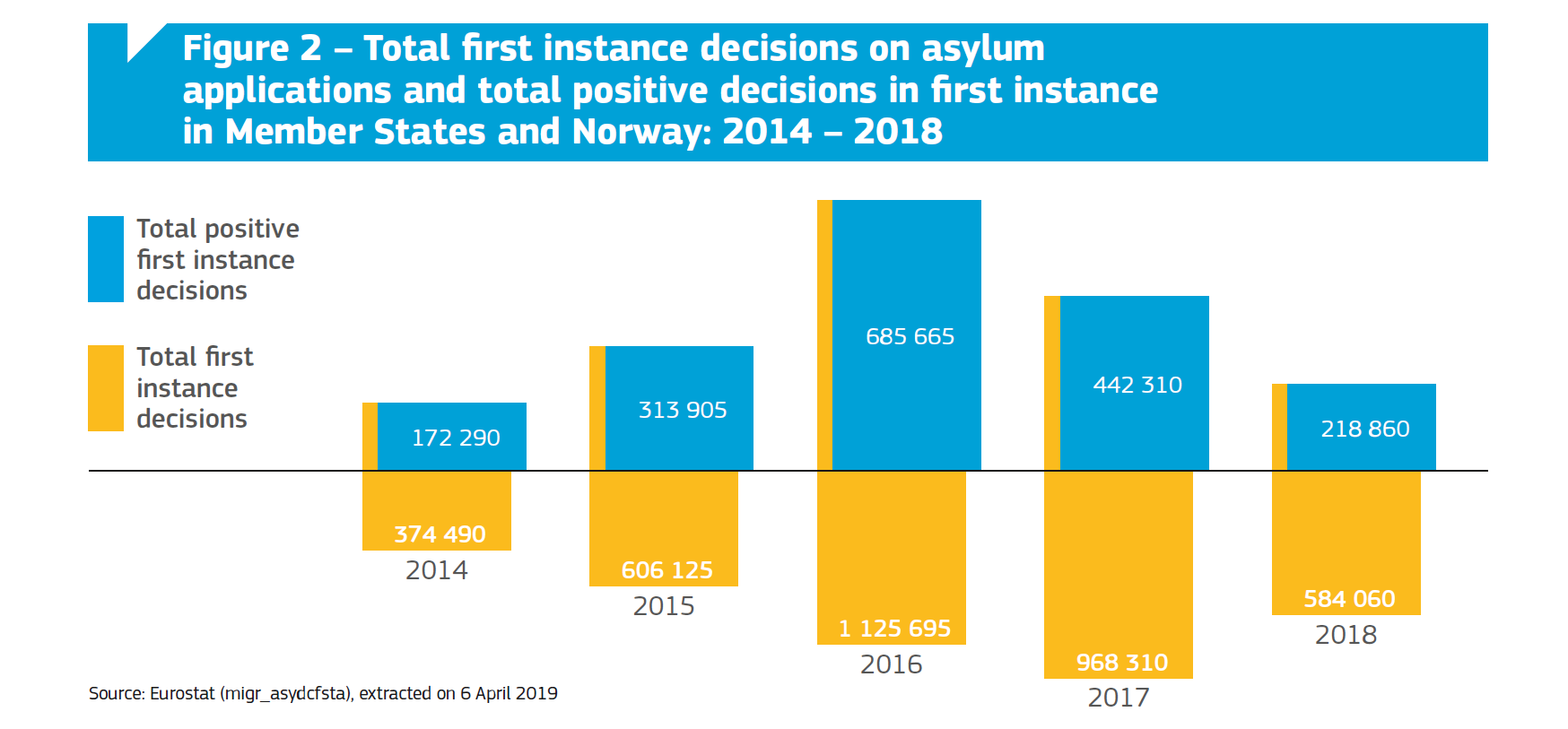

European Commission has declared the migrant crisis to have ended — the number of applicants as well as beneficiaries of international protection has fallen to pre-crisis levels (see the figure below) — yet, its repercussions will be long-lasting.

During the crisis years, it became clear that the current arrangements do not work and the Common European Asylum System needs to be reformed. Unfortunately, no agreement was reached in 2018 on the precise logic of sharing the burden of looking through applications and receiving beneficiaries. The task of carrying these difficult negotiations forward is left to Europe’s new leaders.

In 2018, eight Member States continued the relocation of asylum seekers from Italy and Greece according to the EU scheme, and others did so based on their own national schemes. Resettlement from Turkey and other countries was also continued. Most often, protection was granted to Syrians.

Last year, Member States reviewed the rights and obligations of applicants for international protection and/or their admission conditions. In the height of the migrant crisis, officials were grappling with a huge number of unfounded applications for international protection (48,2% in 2015; 39,1% in 2016; 54,3% in 2017. See the figure above). In order to determine the origin and migration route of the applicants, border guards of several Member States now have the right to examine applicants’ personal communication devices, including the contents of their mobile phones. Also, several Member States extended their lists of safe countries of origin, which are used to filter out unfounded applications and focus on applicants with a genuine need for international protection.

Irregular migration and return

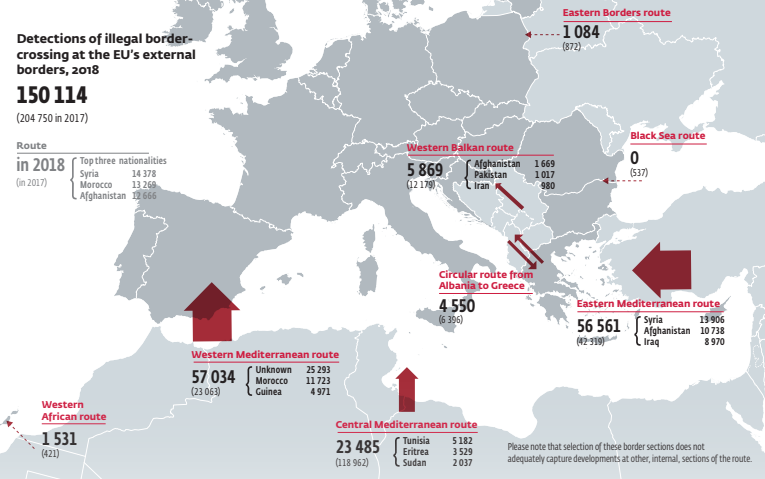

The outgoing European leaders were vigorous advocates for improving the security of EU’s borders. In 2018, there were 150 000 irregular entries detected on the external borders of the EU (see Frontex Risk Analysis for 2019). This is the lowest number in the last five years.

And yet, even while the Central Mediterranean route was largely shut down, irregular immigration via the Eastern and Western Mediterranean routes increased (see the figure above). In order to regain control, cooperation between officials across Member States as well as with officials in third countries (e.g., Turkey or African states) was sought. However, these cooperative measures still need to be stabilised.

In order to increase the efficiency of border control, last year saw the adoption of new strategic documents and various trainings for officials. It also brought further development of the Schengen Information System that enables officials to identify foreign nationals who are subject to expulsion, have been issued an entry ban, need to be arrested due to safety concerns, etc. States acquired new equipment for border monitoring, document authentication and identify verification. Also the construction of physical border barriers continued in 2018.

While human smuggling and trafficking might seem a rather remote concern from the Estonian perspective, this is where many Member States faced some of their greatest migration-related challenges in 2018. In order to save lives, information campaigns were organised to make potential irregular immigrants aware of the hardships of entering and living in Europe without a legal basis, but also of the channels of legal immigration and opportunities for self-realisation in their countries of origin.

The continued stay of immigrants who have been issued a return decision has posed a challenge for years, whilst undermining the legitimacy of granting international protection in the eyes of the local population. In order to increase the effectiveness of return, several Member States extended the range of officials who can issue return decisions and also the list of grounds for issuing an entry ban. Efforts to distribute information about voluntary return were stepped up in 2018. Frontex coordinated several joint return operations with the Member States.

One underlying thread in combating irregular immigration that gained prominence in the last year is cooperation with third countries: this involved trainings for third-country border guards, aid for developing IT systems in third countries, supporting the work of reception and detention centres, conducting joint border guarding operations. There were also joint identification missions in Europe in order to provide immigrants with the identity documents needed for their return to their countries of origin.

Conclusion

Outgoing members of the European Parliament and Commission leave behind several positive developments, but also several challenges. In order to overcome the difficulties and prevent future crises, the newcomers need to have a clear vision and firm determination in all the main fields of migration policy — making Europe more attractive in the eyes of highly-qualified workers, developing a fair and efficient asylum policy, integrating those foreign nationals who have a long-term right of residence as well as thwarting and returning irregular immigrants. In virtually every field, the European Union needs to think globally and cooperate with third countries.

Find out more from the EMN Annual Report on Migration and Asylum; also, check out its inform and the Estonian national report.

Marion Pajumets